As part of our end-of-year celebrations, we're digging into the archives to pick out some of the best Time Extension content from the past year. You can check out our other republished content here. Enjoy!

Although today's gaming landscape is dominated by Nintendo, Sony and Microsoft, there have been plenty of other companies which have tried - or at least considered - producing their own gaming hardware in the past few decades. Nintendo's former rival Sega and industry trailblazer Atari are perhaps the most famous names, but we've also had companies like SNK (the Neo Geo AES and CD), Panasonic (the 3DO Multiplayer), Hudson Soft (the PC Engine family), Taito (the unreleased WOWOW) and Bandai (the Apple Pippin), all of whom have, at some point, tried to enter the domestic gaming hardware arena and experienced wildly differing degrees of success.

Another established name in the industry which had ambitious plans for the living room is Capcom, creator of million-selling franchises like Resident Evil, Mega Man and Street Fighter. Having enjoyed a particularly profitable relationship with Nintendo during the days of the NES and SNES, Capcom could have been forgiven for looking at Nintendo's gargantuan profits and wanting some for itself. In Japan, Nintendo enjoyed a period of almost total dominance, and while publishers like Capcom naturally benefited from this success, they were also very reliant on Nintendo and were limited from supporting other consoles.

Whatever triggered Capcom's decision to enter the home hardware market during the early '90s, the resultant console was a rather strange proposition. Based on Capcom's CPS1 arcade board and released in such small numbers that it remains incredibly hard to track down today, the CPS Changer's muted Japan-only release means that few people have even heard of it. The system was a move by Capcom to leverage its enviable stable of coin-guzzling arcade hits, and while it didn't achieve the commercial success it perhaps deserved - especially when you consider how popular Capcom's coin-op titles were at the time - it serves as an interesting and often overlooked footnote in the firm's illustrious history.

Released in 1994, the CPS Changer offered a means of playing Capcom's CPS1 titles in the comfort of your own home. The CPS1 board powered such arcade hits as Final Fight, Strider, Mercs and Street Fighter II, and is considered to be one of the most successful coin-op hardware standards of the era. You don't have to look far for potential inspiration for the CPS Changer - arcade rival SNK had already released its Neo Geo system by this time, which used the same software across its arcade (MVS) and domestic (AES) formats. For CPS Changer collector Lawrence "NFG" Wright - arguably one of the world's leading English-speaking experts on the console - the comparison between the Neo Geo and CPS Changer is a reasonable one to make, but is not entirely reflective of what the machine was all about.

"On some levels, the concepts are very similar: a software module is connected to an interface module, allowing the game to be played using controllers and a display," he explains. "It's like any game system in that respect. The differences arise, as they always do, from the details. Most other consoles put the main processor - the CPU - in the base console, and the software module was only software - with rare exceptions, like the Super FX chip which powered the likes of Star Fox on the SNES. The CPS Changer used self-contained systems, so each software module had its own CPU, audio amplifier, ROMs and everything needed to operate without any extra electronics. The CPS Changer system itself was more of an adaptor than a console - it didn't add anything but different connectors. If you imagined a console that had one built-in game and a single connector for all your inputs, that's exactly what these modules are, and what most arcade boards are. The connector on the end of the module has power and controller inputs and audio/video outputs, and they'll work in any standard arcade cabinet as a direct replacement game board."

Simply put, the CPS Changer was a means for Capcom to sell its arcade titles to a consumer audience which might not have the expertise or knowledge to pursue other avenues - such as expensive, custom-made SuperGun systems which allowed JAMMA arcade boards to be hooked up to a standard television set. "What the CPS Changer did was take this commercial-grade system and make it home-friendly," Wright continues. "Instead of unusual technical connections, it presented the player with a familiar interface. A small power supply that connected mains power to the system, SNES controller ports, and standard AV and S-Video outputs." Compared to most SuperGun systems of the period, it was a much more elegant option - and one which had the allure of being produced by Capcom itself.

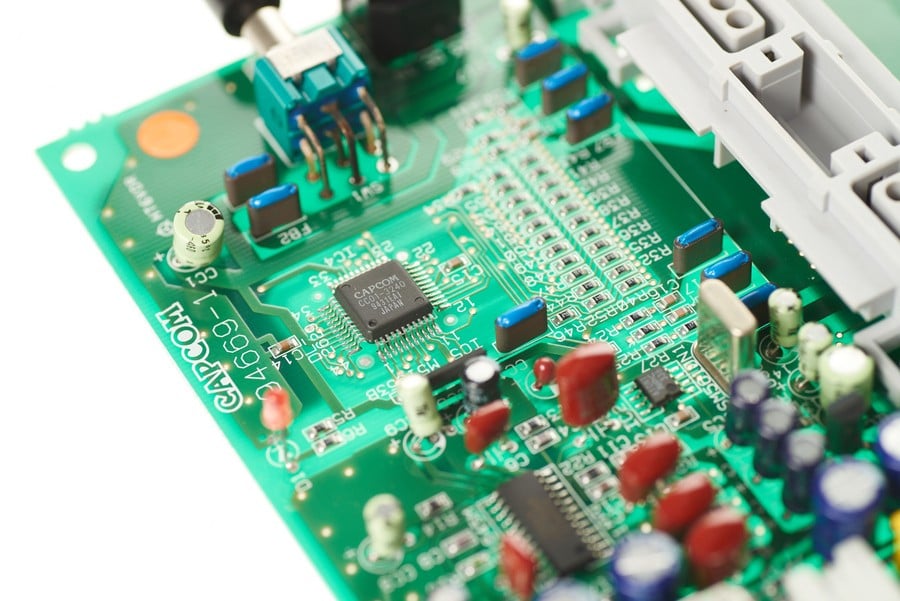

In terms of internal components, the CPS Changer is incredibly simple. "There's a custom Capcom microprocessor which converts the JAMMA controller inputs to SNES compatible signals," explains Wright. "A Sony CXA1645 chroma encoder turns the game's RGB video to S-Video or composite video - both of which were commonplace on Japanese TV sets at the time. And that's it, really - power is provided by an external power brick, and with the exception of supporting parts like resistors and capacitors, the CPS Changer is pretty empty."

The CPS Changer didn't possess its own unique controller but instead used the SNES pad – or any other SNES-compatible controller. For Wright, this choice was most likely down to cost and convenience and is not without precedent. "Japanese manufacturers did this fairly regularly," he says. "Nintendo sold the Super Famicom without a power supply, for example, because it was assumed the players still had their old Famicom at home - the same thing happened recently with the New Nintendo 3DS. Whether they did this because Japanese consumers were relatively capable, or because they wanted to cut costs or - in Nintendo's case - reduce the number of complete Famicom systems entering the used market, is left to the reader to decide."

In the case of the CPS Changer, it made sense to use the pad which belonged to what was - at the time - Japan's most popular system. It also didn't hurt that the SNES / Super Famicom pad was, and still is, one of the best in the business. "Super Famicom controllers were cheap and easy to find, and they were very good quality," Wright explains. "Capcom did release the Capcom Power Stick Fighter, primarily for the Super Famicom audience, but of course, it also worked on the CPS Changer and was a very capable arcade-style joystick which I recommend on its own merits."

Capcom's distribution method for the CPS Changer was also unique. Sold exclusively via magazine adverts in Japanese gaming publications, the system could only be purchased directly from the company itself. The initial bundle included the console, a Capcom Power Stick Fighter joystick and a copy of Street Fighter II': Hyper Fighting. This pack cost 39,800 Yen (£215 / $332 / €293), while additional games would set you back 20,000 Yen (£108 / $167 / €147) apiece. A cheaper hardware bundle - without the Power Stick Fighter - was also made available. Although Capcom had plenty of CPS1 titles to choose from, the CPS Changer's selection of games was incredibly limited. "The library topped out at 11 games," says Wright. "They're rare as far as absolute numbers are concerned, but if you're in Japan, a handful will show up in auctions every year."

Thankfully, those who did take the plunge found that the CPS Changer was capable of accepting non-Capcom titles, and this granted access to a much wider range of arcade software. "You could use any JAMMA-standard game board with the system," Wright explains. "They didn't all work perfectly because of small differences in the connector pinout - the biggest issue was with the controller inputs being moved around - but I've used my CPS Changer with a dozen different non-Capcom games. It's a little wobbly sometimes - the CPS Changer was designed to fit a very specific module shape, and so it sort of balances precariously on boards it wasn't designed for. For this reason, I made a JAMMA extension cable that allows me to space the game and the CPS Changer some distance from each other."

While solid sales figures are not forthcoming, it's fair to assume that the CPS Changer was not a commercial triumph for Capcom and support for the system died off within a year - although the company was generous enough to send it out with a bang rather than a whimper. A cut-down version of Street Fighter Zero (Alpha in the west) - a CPS2 title released in 1995 - would serve as the CPS Changer's swansong and a gift to those loyal fans who had been dedicated enough to purchase the hardware.

"The game was first released on the new, superior CPS2 hardware, but Capcom back-ported it to the CPS1 hardware with a few sacrifices and sold it to the CPS Changer owners," Wright says. Costing 35,000 Yen (£189 / $292 / €258) - almost twice the price of other CPS Changer software - the port lacked animation frames and other elements but would prove to be a significant release in later years. "Interestingly, this move helped emulator authors open up and emulate the new CPS2 system, because the CPS Changer release was largely identical but lacked the difficult encryption found in the CPS2 system," Wright says. "They were able to compare the two systems and work out the tricky bits."

Hindsight is a wonderful thing, but it's hard to imagine that anyone at Capcom back in '94 genuinely expected the CPS Changer to gain mainstream appeal and bumper sales. Wright feels that the release of the system is indicative of the wildly experimental period the Japanese tech industry found itself in at the time. "It was a time of weird stuff in Japan," he says. "The Japanese bubble had only just popped, and Japanese companies were still flush with cash and no crazy ideas were too crazy. Look at the Sharp X68000 computer system, the Nissan Skyline R32, the Sony Minidisc and so on. Japan was a country dedicated to insane toys, and so we got the CPS Changer. It was hardly the weirdest thing released at the time."

Whatever the reason for the birth of this unique and ill-fated console, the legendary nature of its creator and the tiny numbers it was produced in mean that it has gained considerable fame with hardcore retro collectors seeking the ultimate prize. As someone who has lived the dream and owns a CPS Changer himself, Wright is perfectly positioned to comment on collecting for this Holy Grail of obscure game consoles. His advice is simple, but won't come as much comfort for those seeking out this elusive piece of hardware. "Be patient and get a second job," he says with a smile. "There aren't many for sale at any given time, they're not cheap anymore, and there are a lot of other people who want one, too."

Thanks to Lawrence Wright for not only giving up his valuable time to speak to us but also for providing the gorgeous photos you see on this page.

This article was originally published by nintendolife.com on Wed 25th February, 2015.

Comments 45

really cool idea

Hmmm......

Now this is something I never knew existed. Thanks for sharing.

Great article,I had no idea this existed.

"The Japanese bubble had only just popped and Japanese companies were still flush with cash and no crazy ideas were too crazy. Look at the Sharp X68000 computer system, the Nissan Skyline R32, the Sony Minidisc"

I had a Minidisc player and Hifi and I absolutely loved them.,the sound quality was fantastic.At the time I first got my player I told everyone this was the future,even though I was the only person I ever knew who used them.Still didn't stop me from spending ₤450 on a hi fi that served me well for many years,it seemed to get better with age too.Good to know I was an owner of such niche items,just like the Dreamcast was and the Wii U will be.

very cool and with all my readings about Nintendo and sage in the 80s-90s never heard of that.

I have to have this. I never knew Capcom made a console.

But I have to have it.

Interesting, I didn't know this existed.

So it' essentially a Neo Geo AES. Interesting.

@OorWullie I also owned a Mini-disc player. It and quite a few blank mini-discs served me well for quite a few years until I purchased a second generation iPod for Mac. The quality was better, but the transfer process was a bit painful (my mini-disc player was one of the early models).

I'm just amazed that it uses SNES pads. That's pretty damn cool.

So, based on its hardware concepts...its basically a console with "infinite potential" as the game itself brings all the hardware with it ?

Not all that different to an actual arcade cabinet.

But yeah...the golden age, when Capcom ruled the gaming world.

I miss them so darn much...

I guess the system itself is impossible to track down for a mere mortal ?

Even more reasons to finally build my own, dedicated MAME machine :3

I'm actually pretty impressed with this. The pricing doesn't even seem too bad for arcade-perfect: an idea that no one cares about now but was a big deal back then.

Never knew about this, but I have used that controller.

Excellent article. Thanks for this. The 90s were very interesting for what electronics companies could do. I remember the waning years of short-wave radio production, with some models out there that just bolted on a ton of toys. What a great time.

Interesting. There were a lot of unique things done in Japan.

One note — Are the price conversions historic or current. For example, the value of the Yen was actually higher against the dollar in 1994 ($1 USD varied between 97yen to 112yen) than it is presently ($1 USD=118yen) .

Neato

@mike_intv They're current, as I don't have a time machine.

Well I've certainly never heard of this thing

Great article. Never heard of this before.

I want this! I don't care if I have the emulators to all the games Capcom has in the past. I want this dangit! This is my first time hearing of an actual console from Capcom. I would have BEGGED my parents to get me this. Hahaha Thanks @Damo for the read man. Great news!

@Rafie You're welcome! Thanks for the kind feedback

Since its Capcom it was probably the first console that ever had "locked on console DLC" lol

Hey, I'm just amazed they didn't manage to release two mainline Mega Man games and roughly 16 spinoffs during that brief, glorious moment in time.

I own a CPS2 board (Mighty Pang) but I had no idea that this CPS1 changer even existed.

Those games weren't cheap I can see why it had limited success even in the land of the rising sun.

On a side note, anyone actually know anyone who had a NEO-GEO? The games were so expensive even back then.

I learned of this a couple of years ago and was researching it a bit again just a few weeks back. Very interesting stuff. The Changer being a supergun basically is a good indicator it wasn't meant to be mass market. I wonder what Capcom was expecting to sell and how much they actually did. With this thing coming out in 1994, Spring or Summer I think, there wasn't much of a head start against the Saturn and Playstation which would be out in Japan by the end of the year, and those could handle CPS2 games, especially the Saturn. Of course, with the Changer not actually containing hardware to run the game, it could have eventually received CPS2 games, but I suspect those were super expensive in the mid 90s. Nice to be able to own arcade-quality games and not have to worry about suicide batteries and such.

STREET FIGHTER ZEROOOOO!!! ... TWO!

What a fantastic read! Great job, Damien!

It's crazy how many companies have tried to get in on the console business only to find, it isn't easy.

Wow, I would not mind having this at all.

Another great N life article...I never knew this existed!!

Cool... dem SNES controller ports doe.

@Darknyht

Count me in, too. I also had a portable mini disc player (I was living in Japan from 1993 to 1996) and a small stereo. Well above tapes in terms of quality and size.

Amazing! I've been playing games for almost 25 years and I've learned in one year two video game consoles I had never knew existed. This, and the Nuon.

I was gonna say the system looked like a cheap Uzebox enclosure (google it) but after reading the artical, I'm quite impressed.

My friend owns one.

Didn't know about this and now I want one

Great read, cheers! Never heard of this before.

Never heard if this, interesting article, thanks

Even today, I'd genuinely buy something like this. I'd love an official home system that played the genuine Capcom, Sega and Tecmo arcade games.

I wish the inside of the 3DS cartridge looked like that second to last picture. Now that would be something.

Real gaming is about this.

@Damo I think Panasonic might get incorrectly credited for the 3DO.

The 3DO Company made the 3DO. How the console was made, was going with a PC-like structure where anyone can make one. Except that unlike IBM, 3DO put a licensing system on it, and Panasonic was the most ubiquitous of the three companies to bite on it. Goldstar (now known as LG) also made one and released it a year later (though it sounds like a few games had some bugs such that they'd only work on Panasonic consoles), and Sanyo announced one but I don't know if theirs ever made it to market.

I've heard the WOWOW hardware got repurposed into one of Taito's arcade boards (the F3, I think?). One of the canceled F3 games dumped a couple years ago (Recalhorn?) I think is one game suspected of WOWOW origins when it seems like Taito couldn't rework it into a suitable arcade game (one unfairly difficult enough to siphon our quarters ). Seemed like a nice game, too bad they didn't consider a console port.

@AkaLink77 @PugHoofGaming I suspect reuse of the SNES controller ports was probably done so Capcom could also repurpose those arcade stick controllers they had made.

@KingMike The intention wasn't to 'credit' them with the 3DO, it was more to illustrate that they were one of many 'big' tech firms getting involved with home gaming hardware.

However, it's perhaps easy to ignore the fact that Panasonic's support got 3DO over the line in those early days - the company was one of 3DO's most high-profile partners (and Panasonic's parent company, Matsushita, bought the rights to M2 from 3DO, lest we forget) and produced the first 3DO system.

@Damo Unfortunate the M2 ended up being relegated to a few arcade games (most or all of them from Konami, I think) and most significantly, automated banking machines.

Tap here to load 45 comments

Leave A Comment

Hold on there, you need to login to post a comment...